The New Geography of Environmental Education: How Leading Universities Shape a Sustainable Future

Environmental education has moved from the margins of academia to the center of global strategy, and by 2026 it has become one of the clearest indicators of how seriously societies are preparing for a climate-constrained, resource-tight, and socially complex future. Across continents, universities are no longer simply teaching environmental science; they are redesigning how health systems function, how cities grow, how food is produced, how businesses operate, and how technology is governed. For readers of World's Door and visitors to worldsdoor.com, this transformation connects directly with interests that span health, travel, culture, lifestyle, business, technology, and the evolving ethics of global society, because sustainability now threads through each of these domains in ways that are both practical and deeply personal.

Why Sustainability Education Matters More in 2026

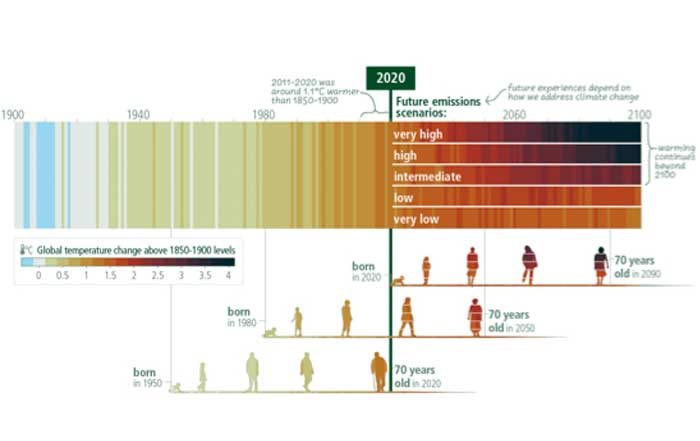

In 2026, the urgency of climate change, biodiversity loss, and environmental injustice is no longer an abstract scientific forecast but a lived reality. Intensifying heatwaves in Europe and North America, shifting monsoon patterns in Asia, wildfires in Australia and Canada, water stress in parts of Africa and South America, and rising sea levels affecting coastal cities worldwide have made environmental literacy a prerequisite for resilient societies. Institutions such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), whose synthesis reports can be explored through the IPCC website, have underscored that keeping global warming as close as possible to 1.5°C requires not only technological solutions but also new forms of governance, finance, and education.

Environmental education has therefore evolved into a deeply interdisciplinary field that integrates climate science, public health, urban planning, economics, law, ethics, and digital innovation. Leading universities now design programs that address the connections between planetary health and human health, an approach championed by organizations like the World Health Organization, where readers can learn more about environmental health. This shift is mirrored in the editorial philosophy of World's Door, where topics such as health, business, technology, and environment are increasingly framed through the lens of long-term sustainability and societal resilience.

Universities as Global Actors in Sustainability

By 2026, the most influential universities in environmental education have become global actors in their own right. Their research programs inform international agreements, their faculty sit on panels convened by bodies such as the United Nations Environment Programme, and their alumni lead climate strategies in governments and boardrooms. Initiatives tracked by the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals framework, explained in depth on the UN SDG platform, are often designed or evaluated with input from these academic centers.

The top environmental institutions also play a decisive role in shaping how businesses transition to low-carbon and nature-positive models. Organizations like the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, accessible via its sustainable business insights, frequently partner with universities to develop tools for climate risk disclosure, circular economy design, and just transition strategies. For readers interested in how corporate practice is changing, this is closely aligned with the kind of cross-sector analysis featured in World's Door's coverage of innovation and sustainable transformation.

The Evolving Profile of Leading Environmental Universities

The universities most associated with environmental leadership in 2026 share several characteristics that speak directly to Experience, Expertise, Authoritativeness, and Trustworthiness.

First, they maintain long-standing, peer-reviewed research records in climate science, ecology, environmental economics, and sustainable engineering, often published in high-impact journals such as Nature Climate Change and Environmental Research Letters. These publications, which can be surveyed through platforms like Nature's climate collection, lend empirical credibility to their teaching and policy advice.

Second, they have built large, interdisciplinary schools or institutes dedicated to environment and sustainability. Stanford University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), University of Cambridge, University of Oxford, Yale University, and Harvard University exemplify this trend. Their centers, such as the Precourt Institute for Energy at Stanford and the Environmental Solutions Initiative at MIT, do not operate as isolated academic silos; they bring together engineers, economists, data scientists, lawyers, and public-health experts to work on integrated solutions. Readers who follow technology and climate intersections will recognize that many of the clean-energy and carbon-removal startups emerging in Silicon Valley and Boston trace their origins to these university labs.

Third, these institutions demonstrate environmental stewardship on their own campuses. Universities in the United States, United Kingdom, continental Europe, Asia, and Oceania now treat their estates as living laboratories for low-carbon infrastructure, regenerative landscapes, and circular resource systems. The Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education, whose work is documented on the AASHE website, tracks how universities from the University of British Columbia to ETH Zurich and Wageningen University & Research implement net-zero strategies, sustainable procurement, and biodiversity-friendly planning. Prospective students and professionals increasingly view such operational choices as indicators of institutional integrity.

Finally, leading environmental universities show a consistent commitment to public engagement. They offer open online courses, collaborate with NGOs, participate in citizen-science initiatives, and shape public debate through accessible reports and media contributions. Platforms such as edX and Coursera now host numerous sustainability programs designed by these universities, making advanced environmental education available to learners across North America, Europe, Asia, Africa, and South America. This democratization of knowledge aligns with the mission of World's Door to provide readers with gateways to informed, globally relevant perspectives on education and society.

Regional Perspectives: From Global North to Global South

A key development by 2026 is the broadening geography of environmental expertise. While North American and European universities retain significant influence, institutions in Asia, Africa, and Latin America have become indispensable partners in addressing region-specific climate and ecological challenges.

In Asia, universities such as the University of Tokyo and Peking University have strengthened their roles in studying urban air quality, water security, and climate adaptation in megacities. Their collaborations with national ministries and regional organizations contribute to policy frameworks that affect hundreds of millions of people. For readers interested in Asia's environmental trajectory, policy updates from bodies like the Asian Development Bank, available through its climate and environment hub, provide context for how research translates into infrastructure and resilience investments.

In Africa, the University of Cape Town has become a focal point for climate and development research that addresses food security, water scarcity, and urban vulnerability. Its African Climate and Development Initiative works closely with regional governments and the African Union, whose climate change programs outline continent-wide strategies. This regional expertise is critical for understanding how global climate finance and adaptation plans must be tailored to local social and cultural realities, a theme that resonates strongly with World's Door's coverage of society and world affairs.

In Latin America, the University of São Paulo and other research centers in Brazil, Chile, and Colombia are central to debates over Amazon conservation, sustainable agriculture, and just energy transitions. Their fieldwork informs global understanding of tropical forests as carbon sinks and biodiversity reservoirs. Readers can follow broader regional trends through organizations such as the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, which shares environmental and development analysis on the ECLAC website.

Meanwhile, European universities including ETH Zurich, Wageningen University & Research, the University of Copenhagen, and the University of Edinburgh contribute to policy design within the European Union, particularly around the European Green Deal and nature-restoration laws. The European Environment Agency, accessible via its climate and energy pages, regularly cites academic work from these institutions in its assessments of progress toward net-zero and resilience targets.

The New Skill Set: What Environmental Graduates Bring to the World

Graduates of leading environmental programs in 2026 enter a labor market that increasingly values systems thinking, data literacy, and ethical judgment. They are trained not only to understand climate models and ecological indicators but also to interpret how these metrics intersect with finance, law, and social equity.

Many programs now require students to engage with climate risk disclosure frameworks such as those developed by the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), whose recommendations are summarized on the TCFD knowledge hub. This prepares graduates to help banks, insurers, and asset managers quantify and manage climate risks, a skillset that is in high demand in financial centers from New York and London to Singapore and Sydney. For readers of World's Door interested in sustainable investing and corporate strategy, this is a direct bridge between academic expertise and boardroom decision-making.

In parallel, environmental curricula increasingly emphasize environmental justice and ethics. Courses draw on work from organizations like Human Rights Watch, which documents the human consequences of environmental degradation on its environmental justice pages, and from think tanks such as the World Resources Institute, whose data and analysis inform debates on land use, water security, and urban resilience. This ethical grounding aligns with World's Door's commitment to exploring ethics and the cultural meanings of sustainability across different societies.

Technical skills are equally important. Students gain experience with remote sensing, geographic information systems, and AI-driven environmental monitoring, often using open data from platforms like the European Space Agency's Copernicus program. They learn to model urban heat islands, track deforestation, or optimize renewable-energy grids, capabilities that feed directly into careers in city planning, energy systems, and conservation technology. For readers following developments in smart cities and green infrastructure, these are the skill sets behind many of the innovations covered in World's Door's sections on technology and lifestyle.

How Environmental Education Shapes Everyday Life

While the work of leading universities often appears in policy documents and scientific journals, its effects are increasingly visible in everyday life across the countries and regions that World's Door readers care about, from the United States, United Kingdom, Germany, and Canada to Japan, Singapore, South Africa, and Brazil.

In health, research from universities and public-health institutes has clarified the links between air pollution, heat stress, mental health, and chronic diseases, reinforcing the importance of clean air and green spaces in cities. Resources from the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change, presented on the Lancet Countdown site, demonstrate how academic findings inform hospital preparedness, public-health advisories, and urban design standards. This knowledge shapes personal decisions around where to live, how to commute, and what protective measures to take during extreme weather, themes that intersect directly with health and lifestyle content on World's Door.

In travel and culture, environmental education influences how destinations are managed and experienced. Universities collaborate with tourism boards and local communities to design low-impact tourism models, protect cultural heritage in climate-vulnerable regions, and promote nature-based experiences that support conservation financing. Organizations like the Global Sustainable Tourism Council, whose criteria are outlined on the GSTC website, rely on academic input to define what responsible travel looks like in practice. Readers planning trips or exploring cultural narratives around nature will recognize how these frameworks shape the guidance shared in World's Door's travel and culture features.

Food systems are also being reshaped by research from environmental universities. Studies on soil health, regenerative agriculture, and sustainable fisheries inform everything from supermarket sourcing policies to restaurant menus and household choices. Institutions collaborate with organizations like the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, which provides extensive data on sustainable food and agriculture, to design pathways that feed growing populations without exceeding planetary boundaries. For readers who follow culinary trends and food ethics, this scientific foundation underpins much of the analysis presented in World's Door's food coverage.

Trust, Transparency, and the Role of Independent Media

As sustainability becomes a central theme in politics and business, the credibility of environmental information is more important than ever. Universities contribute to trustworthiness by adhering to peer-review processes, disclosing methodologies, and subjecting their work to external scrutiny. Repositories like Google Scholar and institutional open-access archives allow the public to trace claims back to underlying research, reinforcing transparency.

Independent media platforms also have a responsibility to interpret this complex information responsibly. For World's Door, this means curating stories that connect rigorous academic insight with practical implications for readers' lives, whether the subject is decarbonizing transport in Europe, water resilience in Australia, urban greening in North America, or community-based conservation in Africa and Asia. By linking to primary sources, highlighting diverse regional perspectives, and grounding coverage in verifiable data, the platform strengthens its own authoritativeness and deepens the trust relationship with its global audience.

Looking Ahead: The Next Frontier of Environmental Education

By 2026, environmental education has already expanded beyond traditional classrooms and laboratories, but its evolution is far from complete. Several trends are likely to define its next phase and will be of particular interest to the globally engaged readership of World's Door.

One is the integration of artificial intelligence and big data into every aspect of environmental decision-making. Universities are partnering with technology companies and public agencies to develop predictive models for extreme weather, biodiversity loss, and energy demand. These collaborations raise important ethical questions about data governance, algorithmic bias, and accountability, questions that will require close attention from ethicists, lawyers, and social scientists as much as from engineers.

Another is the growing focus on social resilience and psychological adaptation. As climate impacts intensify, universities are beginning to explore how communities can maintain social cohesion, cultural identity, and mental wellbeing in the face of disruption. Research on climate anxiety, migration, and conflict is informing new types of curricula that blend environmental science with psychology, anthropology, and peace studies. This is particularly relevant to regions experiencing rapid climate-induced change, from small island states in the Pacific to drought-prone areas in Africa and heat-stressed cities in Europe and North America.

A third emerging trend is the embedding of sustainability into general education for all students, not only those specializing in environmental fields. Leading universities are making climate literacy, basic ecological understanding, and ethical reflection on technology and consumption integral to undergraduate education in business, law, medicine, and the arts. This whole-institution approach reflects the reality that every profession now has an environmental dimension, whether in supply-chain management, urban design, food systems, or digital infrastructure.

For readers of World's Door, these developments mean that sustainability will continue to shape the stories, analyses, and practical guidance offered across sections-from how businesses in Germany, the United States, and Singapore are rethinking growth, to how communities in South Africa, Brazil, and Scandinavia are building new models of shared prosperity within planetary limits.

Conclusion: Opening Doors to a Sustainable Future

The leading universities in environmental education have become essential pillars of the global response to climate and ecological crises. Their authority rests on decades of research, interdisciplinary teaching, and engagement with policymakers, businesses, and communities across continents. Their trustworthiness is reinforced by transparent methods, peer review, and a sustained commitment to public communication.

For a platform like World's Door, which seeks to connect readers with the most consequential developments in health, travel, culture, lifestyle, business, technology, environment, society, and education, these institutions are more than distant centers of expertise. They are active partners in a shared project: to understand how the world is changing and to navigate those changes with insight, responsibility, and hope.

As environmental education continues to advance in 2026 and beyond, its influence will be felt not only in international agreements and corporate strategies but also in the everyday choices people make about where they live, how they move, what they eat, how they work, and what futures they imagine for their families and communities. By following the work of these universities and engaging with trusted sources of analysis, readers can open their own doors to informed, meaningful participation in building a sustainable, just, and vibrant world.